CONNECTED COMMUNITIES

KINgsborough houses

The Exodus and Dance Project is made possible by funding from the Mellon Foundation and the New York City Council

-

The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA), Public Housing Community Fund (the Fund), and the Mellon Foundation are breaking ground in January 2024 on an 18-month restoration effort of historic public art at NYCHA Kingsborough Houses, along with an artist-in-residence program and other place-based interventions.

The grant to the Fund will support launching an unprecedented place-based art conservation project at Kingsborough Houses, one of NYCHA’s key developments in the historic Weeksville community of Brooklyn. The program’s efforts are based on participatory planning and design and strive to enhance physical and social connections between residents and their communities.

A Kingsborough Houses Stakeholder Advisory Group, local cultural institutions, and Community-Based Organization partners will inform this project. Jemco Electrical Contractors, Evergreene Architectural Arts, Ronnette Riley Architect, Jablonski Building Conservation, Inc. Fisher Marantz Stone Architectural lighting designers will lead the restoration effort for NYCHA and the Fund between December 2023 and July 2025.

-

Frieze Restoration: The project's first phase involves the restoration of the frieze, Exodus and Dance. The 18-month restoration involves carefully removing the frieze from the wall and transporting it to a conservation studio. Additional work includes:

(1) Building a new wall to serve as the base of support for the frieze.

(2) Replacing the surrounding pavement.

(3) Upgrading the site lighting for the frieze.

Community Engagement and Cultural Preservation: The project's second phase centers on community engagement and storytelling. The project will unveil a place-based strategy that highlights shared histories and memories. It includes art installations, community murals, and interpretive signage or storywalks that will serve as mediums to reflect the voices and narratives of the community and the significance of Exodus and Dance. The project will preserve the rich cultural heritage of Kingsborough Houses and the broader community.

Placemaking: The final phase will result in a renovated plaza around the artwork, which will be transformed into a vibrant public space, fostering community gatherings, performances, and activities, contributing to the overall quality of life for NYCHA residents with lighting.

Restoration Groundbreaking

Restoration Timelapse

Year in Review (2024)

Art and Community Engagement

Ifeoma Ebo and Jerome Haferd, lead artists | Pedro Cruz Cruz, Violet Greenberg

Year

FALL 2025

PROJECT

IN PROGRESS

Partners

Public Housing Community Fund, New York City Housing Authority, Fulton Art Fair, Weeksville Heritage Center | Fabrication and Consultants | 618 Design, Franpen Restoration, Lempira Restoration Inc. Bartholomew Lighting, Leni Schwendinger Light Projects

Artwork Content Sources

Family Feud Game: Our Migration Stories | Individual & Focused Resident Interviews | Community Lantern Design Workshop

"Migration," a living history inspired by Exodus and Dance

DESIGNERS

LEARN MORE

-

Richmond Barthé was born January 28, 1901, in Bay St. Louis, MS. He studied painting at the Art Institute of Chicago (1924-1928) before moving, in 1929, to New York City. Barthé collaborated with other artists and intellectuals while working for the Harmon Foundation and Works Progress Administration. Barthé was a prominent figurative sculptor of the Harlem Renaissance. In 1949, he relocated to the Caribbean, where he worked on the statue of Toussaint L'Ouverture at the National Palace in Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Afterwards, he traveled to Europe to further refine his craft. He passed away on March 5, 1989 (age 88 years) in Pasadena, CA.

-

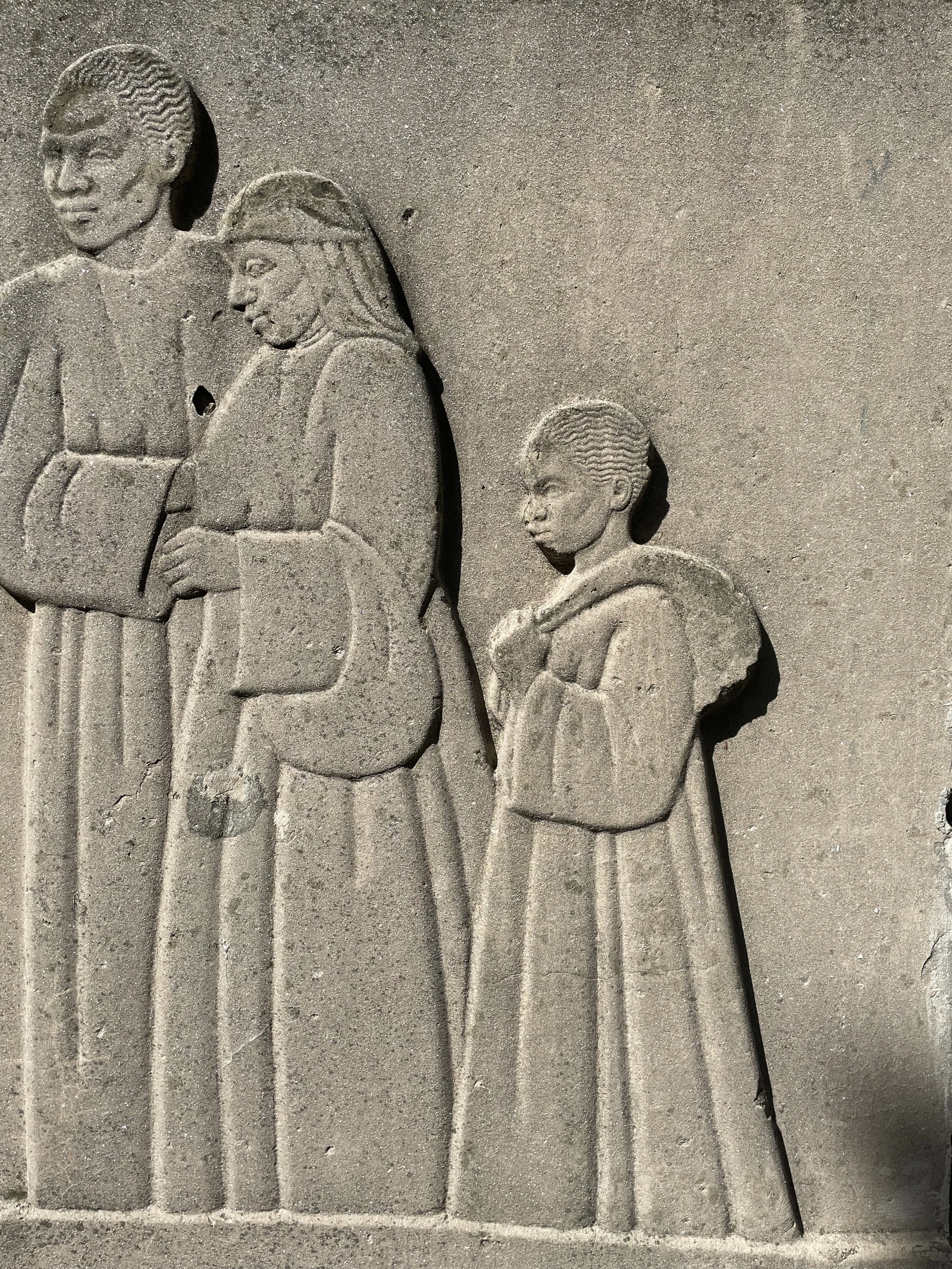

Spanning over 80 feet, this artwork exemplifies Richmond Barthé’s unique approach to his work, integrating elements of movement to convey a sense of communal joy. The art captures the vitality and rhythm of dancing figures in celebration and migration on a concrete bas-relief frieze. Completed in 1939, and inspired, in part, by Marc Connelly’s Broadway play “The Green Pastures,” a story that portrays episodes from the Old Testament through the lens of the rural black south. The artwork was initially slated to be part of an amphitheater at The New York City Housing Authority (NYCHA) Harlem River Houses. NYCHA decided to feature the work on a wall at Kingsborough Houses.

-

Construction of the Kingsborough Houses finished in 1941. The landscape architect Gilmore Clarke designed the development's grounds in a style resembling a city park.

Shortly after, the Kingsborough Extension was finished in 1966 for senior citizens’ housing.

-

Weeksville: Past Forward. https://www.groundswell.nyc/projects/weeksville-past-forward-247

Amistad Research Center. “Barthé, Richmond, 1901-1989.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://amistad-finding-aids.tulane.edu/agents/people/279.

Amon Carter Museum of American Art. “Richmond Barthé’s The Negro Looks Ahead Acquired by the Amon Carter Museum.” Accessed December 7, 2023. https://www.cartermuseum.org/press-release/richmond-barthe-negro-looks-ahead-acquired-carter-museum.

Curator, Samella Lewis, Ph.D. “Richmond Barthé: Harlem Renaissance Sculptor.” Richmond Barthé: Harlem Renaissance Sculptor, 2023. https://a-r-t.com/barthe/.

Richmond Barthé: African-American Sculptor (1901-1989), 2009. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=43Z79gCYhttps://a-r-t.com/barthe/AEU.

Summers, Martin. “Richmond Barthé (1901-1988),” November 19, 2007. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/barthe-richmond-1901-1988/.

The Art Institute of Chicago. “Richmond Barthé,” 1901. https://www.artic.edu/artists/1678/richmond-barthe.

Bearden, Romare, and Harry Henderson. A History of African-American Artists: From 1792 to the Present. 1st ed. Pantheon Books, 1993.

Evans, Curtis J. “The Religious and Racial Meanings of The Green Pastures.” Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation 18, no. 1 (2008): 59–93. https://doi.org/10.1525/rac.2008.18.1.59.

GLBTQ Archives. “Archived Arts Encyclopedia Entries: James, Richmond Barte.” Accessed November 28, 2023. http://www.glbtqarchive.com/artsindex.html.

NYC LGBT Historic Sites Project. “Richmond Barthé & ‘Green Pastures: The Walls of Jericho.’” Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.nyclgbtsites.org/site/richmond-barthe-green-pastures-the-walls-of-jericho/.

Reaven, Marci, and Steven J. Zeitlin. Hidden New York : A Guide to Places That Matter. Rivergate Books, an imprint of Rutgers University Press, 2006.

“Restoring Historic Art at Kingsborough Houses - NYCHA Now,” February 1, 2021. https://nychanow.nyc/restoring-historic-art-at-kingsborough-houses/.

“Richmond Barthé (1901-1989) - Artists - Michael Rosenfeld Art.” Accessed November 28, 2023. https://www.michaelrosenfeldart.com/artists/richmond-barth-1901-1989/selected-works/1.

“Selected Works - Richmond Barthé (1901-1989) - Artists - Michael Rosenfeld Art.” Accessed November 29, 2023. https://www.michaelrosenfeldart.com/artists/richmond-barth-1901-1989/selected-works/1#public-collections_21.

Swann Galleries News. “The Elegant Sculptures of Richmond Barthé,” May 27, 2020. https://www.swanngalleries.com/news/african-american-art/2020/05/the-elegant-sculptures-of-richmond-barthe/.

The Johnson Collection, LLC. “Richmond Barthe.” Accessed November 29, 2023. https://thejohnsoncollection.org/richmond-barthe/.

Vendryes, Margaret Rose. Barthé: A Life in Sculpture. Univ. Press of Mississippi, 2008.

Visiting Richmond Barthé Mural in Brooklyn, NY, with Swann Galleries, 2022. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jk5ztF2SRrM.